L'interpretazione dei... sintomi | The interpretation of... symptoms

- ellemmelle

- 26 mar 2020

- Tempo di lettura: 8 min

Aggiornamento: 26 mar 2020

English version below

L'interpretazione dei... sintomi

Testo di Maddalena Brentari, con una traduzione di Lisa Bragantini

L’ennui, Gaston La Touche (1893)

Chi l’avrebbe mai detto che un giorno avremmo salvato il mondo restando in pigiama? Sembra quasi un paradosso, ma in tempi di quarantena, se la migliore cosa da fare per noi stessi e per il resto del mondo è stare a casa comodamente agghindati, non ci resta che obbedire. E approfittarne. Cosa fare allora per combattere la noia e la malinconia, specialmente in una casa vuota?

Chiaramente, il mondo di oggi, con il suo avanzatissimo livello di tecnologie, ci offre un numero vastissimo di passatempi con cui riempire le nostre giornate. Ma per quelli che, con tutto questo tempo fra le mani, sentono il bisogno di ritrovare il contatto con qualcosa di autentico, non dimentichiamoci che le primissime risorse per farci evadere dalla situazione attuale sono i monumentali classici della letteratura italiana e straniera.

Noia. Insoddisfazione. Desiderio di evasione. Questa è l’interpretazione dei “sintomi” più diffusi tra gli italiani che si trovano a vivere questo isolamento forzato.

La cura? Conoscere Emma, l’emblema della noia più profonda, inappagante e infelice.

Jeune femme en bateau, James Tissot (1870)

Madame Bovary è indubbiamente una delle gemme più conosciute della Letteratura Francese: tutti, almeno una volta nella vita, vengono a contatto con l’immensità di questo romanzo, spesso difficile da comprendere nella sua banalità apparente. Pubblicato per la prima volta nel 1856, Madame Bovary è un romanzo realista, avvincente, largamente malinconico e sorprendentemente moderno, che racconta la vita e i sogni dell’infelice Emma Bovary.

L’autore, Gustave Flaubert, usa un linguaggio poetico e dettagliatissimo ed una forma impeccabile ed incredibilmente curata, per descrivere un’esistenza mediocre e un matrimonio insoddisfacente.

Questo capolavoro concettuale ha come punto di forza l’essere, essenzialmente, un “libro sul nulla” (come viene descritto dall’autore stesso in una lettera del 1852), povero di contenuti, che propone la visione di una realtà deludente in netto contrasto con la ricchezza stilistica precedentemente menzionata.

La protagonista, Emma Rouault, è una semplice ragazza di campagna, convenientemente educata in un convento ma profondamente influenzata dalla lettura dei romanzi d’amore a cui si dedicava in gran segreto. Emma sposa un mediocre medico di campagna, Charles Bovary, sognando l’amore che tanto aveva desiderato sfogliando le pagine di quei libri, Tuttavia, nonostante l’adorazione che il marito nutre nei suoi confronti, il matrimonio si rivela lontanissimo dalle sue aspettative romantiche, anche in seguito alla nascita di una bambina. Cercando altrove le passioni amorose tanto desiderate, Emma decide di intrecciare – per noia o per capriccio – due deludenti relazioni extraconiugali.

Oltre all’immaginazione romantica, che distorce la visione della realtà di Emma, l’altra passione dominante della nostra protagonista è l’irrefrenabile bramosia di vivere una vita nel lusso, che ovviamente Charles – nella sua mediocrità – non le può offrire. Dopo essersi lasciata ingannare da un mercante, Emma Bovary si ritrova gravemente indebitata, profondamente sola e irrimediabilmente infelice, e decide di togliersi la vita.

Il romanzo risulterà di sicuro attraente per tutti quelli che, in questa quarantena, non temeranno il confronto con un grande classico e con una interpretazione minuziosa e verosimile della società francese della seconda metà dell’Ottocento. Inoltre, non rimarranno delusi nemmeno quelli che inseguono il gusto del sarcasmo, dello scandalo e della perfezione stilistica, giacché la “paladina dei sogni infranti” è tutto questo, e molto di più.

‘Symphony in White, No 2: The Little White Girl’ (dettaglio), James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1864)

Negli ultimi centosessant’anni, Madame Bovary non ha mai smesso di essere un romanzo sorprendentemente attuale: se il primo a dire “Madame Bovary, c’est moi!” (Madame Bovary, sono io) è stato l’autore stesso, ma nel mondo moderno, moltissime persone si sono trovate a condividere il pensiero di Flaubert. È vero infatti che nella società moderna circolano ancora gli stessi mali di Emma, essenzialmente l’ennui (la noia), il bovarismo (l’insoddisfazione) e il romanticismo dozzinale, o di facciata.

Cosa fare, allora, in questi giorni di isolamento per combattere i pensieri negativi e le brutte abitudini, evitando di trasformarci in una sorta di “Emma moderna”?

Prima di tutto è bene sapere che l’insoddisfazione di Emma è causata dalla sua fervida immaginazione, che confeziona per la nostra sognatrice ingenua degli ideali inarrivabili. Emma, infatti, è incapace di vedere il mondo reale, perché mentre lo guarda finisce inevitabilmente per deformarlo attraverso gli schemi e le trame dei suoi amati romanzi rosa. Per questo, ad esempio, nel realizzare di avere un amante, Emma sente di aver coronato un sogno riconoscendosi in quel tipo di donna che aveva tanto invidiato.

La forza di questo personaggio, però, sta nella sua sensualità: le sue ciglia nere, i suoi occhi bruni, i capelli lungi e corvini, il suo abbigliamento provocante… sono tutti dettagli che contribuiscono alla costruzione di quell’immagine di sé come eroina romantica che pervade l’ingenuità dei suoi sogni. A questi sogni, tuttavia, si contrappone la realtà: “Tutto ciò che la circondava immediatamente […], le sembrava un’eccezione nel mondo, un caso particolare nel quale ella si trovava presa: di là, si stendeva a perdita d’occhio l’immenso paese delle felicità e delle passioni.”

(Da Madame Bovary, G. Flaubert)

In Madame Bovary, il ricordo è bellezza; ma poiché la bellezza dei ricordi è perduta, essa, nello stile di Flaubert, è struggente. La chiave di lettura realista, dunque, si vede soprattutto nella descrizione della desolazione, che riflette il male di Emma, cioè la sua incapacità di accontentarsi di ciò che ha.

Questo è precisamente ciò che noi, eroi ed eroine moderne, dobbiamo cercare di evitare in questi giorni di quarantena: invece di pensare a tutte le cose che in questo momento non possiamo avere perché la situazione attuale ce lo impedisce, concentriamoci sulle cose positive che ci stanno accadendo. Sforziamoci di individuare, nella monotona quotidianità di questa esperienza, tutti gli aspetti positivi di questa situazione, come ad esempio il fatto di avere molti più strumenti a disposizione per combattere l’ennui rispetto alla povera Emma Bovary, primo fra tutti il romanzo a cui questa sciagurata ha dato il nome.

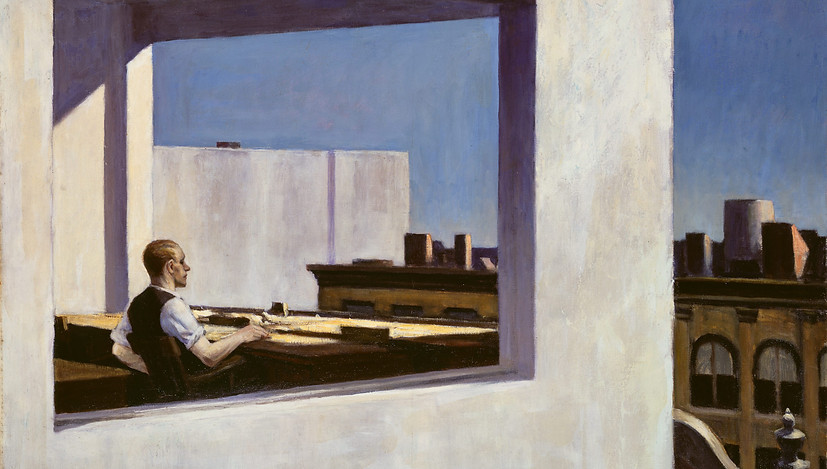

Immagine via Loewe. (2018)

English version

The interpretation of... symptoms

Translated by Lisa Bragantini from the original text by Maddalena Brentari

L’ennui, Gaston La Touche (1893)

Who would have thought that one day we would have saved the world by remaining in our pajamas? It sounds like a paradox but, in times of quarantine, if the best thing to do for us and the rest of the world is staying at home comfortably dressed up, we just have to obey. And take advantage of it. What can we do, then, to fight boredom and melancholy, especially in an empty house? Today’s world, with its high level of technology, clearly offers us a huge number of pastimes by which to fill our days. However, for those that, with so much time on their hands, feel the need to rediscover a connection with something authentic, let’s not forget that the very first resources that can help us escape from the actual situation are the majestic classics of Italian and foreign literature.

Boredom. Dissatisfaction. The desire to escape. This is the interpretation of the most common “symptoms” among the Italians who find themselves to live in this enforced isolation. The cure? Getting to know Emma, the symbol of the deepest, most unquenchable and miserable boredom.

Jeune femme en bateau, James Tissot (1870)

Madame Bovary is indubitably one of the most known gems of French literature: everyone, at least once in their life, comes in contact with this novel’s immensity, often hard to understand in its apparent banality. Published for the first time in 1856, Madame Bovary is an engaging, widely melancholic and surprisingly modern realistic novel that narrates the life and dreams of the unhappy Emma Bovary.

The author, Gustave Flaubert, uses a very detailed and poetic language and a perfect and well-edited form to describe a mediocre existence and an unsatisfactory marriage.

This conceptual masterpiece has as its strength the fact of being “a book about nothing” (as the author himself described it in a letter in 1852), poor in content, which offers the vision of a disappointing reality in clear contrast with the stylistic richness previously mentioned.

The main character, Emma Rouault, is a simple country girl, educated in a convent but profoundly influenced by the reading of romantic novels, which she used to read in great secret. Emma marries a mediocre country doctor, Charles Bovary, dreaming about the love she has always desired leafing through the pages of those books. However, despite the adoration that her husband feels towards her, the marriage reveals to be far from her romantic expectations, even after the birth of a little girl. Looking for the much-desired romantic passions elsewhere, Emma decides, out of boredom or caprice, to establish two unsatisfactory extramarital affairs.

Besides the romantic imagination, which distorts Emma’s vision of reality, the other dominant passion of our main character is the covetousness of living a luxurious life, that Charles, in his mediocrity, cannot offer to her. After being deceived by a merchant, Emma Bovary founds herself seriously indebted, deeply alone and hopelessly unhappy and decides to take her own life.

The novel will be very appealing for those who, in this quarantine, will not fear the confrontation with a great classic and its meticulous and realistic interpretation of the mid-nineteenth century French society. Moreover, even those who search for sarcasm, scandal, and stylistic perfection will not be disappointed because our “heroine of broken dreams” is all this and much more.

‘Symphony in White, No 2: The Little White Girl’ (detail), James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1864)

In the last one hundred and sixty years, Madame Bovary has never stopped being surprisingly actual: if the first one to say “Madame Bovary, c’est moi!” (Madame Bovary, it’s me) was the author himself, nowadays a lot of people found themselves to share Flaubert’s thought. Indeed, it is true that the same diseases Emma’s suffered in the book are still existing in modern society: the ennui (boredom), bovarism (dissatisfaction) and cheap or cosmetic romance. What to do, then, in these days of isolation, to overcome negative thoughts and bad habits, and avoid becoming a sort of “modern Emma”?

First of all, it is important to understand that Emma’s dissatisfaction is caused by her fervent imagination that creates unreachable ideals for our naive dreamer. Emma is unable to see the real world because when she looks at it she ends up distorting it with the schemes and plots of her beloved novels. For this reason, for example, in realizing that she is having an affair, Emma feels that she fulfilled a dream and she identifies herself with the kind of woman she has always envied.

However, the strength of this character is to be found in her sensuality: dark lashes, brown eyes, long and raven hair, provocative clothing... These are all details that contribute to the creation of the imaginary of the romantic heroine that pervades the ingenuity of her dreams. Nevertheless, these dreams are in contrast with reality: “Everything immediately surrounding her [...], seemed to her the exception rather than the rule. She had been caught in it all by some accident: out beyond, stretched as far as the eye could see was the immense territory of rapture and passions.”

(From Madame Bovary, G. Flaubert)

In Madame Bovary the memory is beauty but, since the beauty of memories is lost, in Flaubert’s style it is heartbreaking. Therefore, the realist interpretation is to be found mostly in the description of the desolation, which reflects Emma’s disease, which is her inability to be satisfied with what she has.

This is precisely what we, modern heroes and heroines, have to avoid in these days of quarantine. Instead of thinking about all the things we cannot have because the situation does not allow us to, we have to concentrate on the positive things that are happening to us. In the monotonous everyday life we are experiencing, we have to make an effort to find the positive aspects of this situation, such as the fact of having far more means to fight our ennui, if compared to the ones that the poor Emma Bovary had. First and foremost, we have the novel named after this wretched girl.

Image via Loewe (2018)

Comments